highlighted: Nan Goldin

What’s the first thing or association that comes to mind when you think of Nan Goldin and her work? Assuming, of course, that you are familiar with this artist. If you don’t know her yet, let’s change that right now.

As someone who has long admired her photographs for their unposed intimacy and the deep connection they create to Nan Goldin’s biography and her surroundings, I have to think of exactly that. The sense of dis-order her works evoke has spoken to me ever since I first stumbled across them.

Mind you, I don’t know exactly where I came across her work for the first time—it could have been a group show at C/O Berlin or as part of some university studies. But I do remember during what time in my life. It was several years ago, around 2018 or 2019, just after I had freshly moved to the German capital—known to everyone as the city of freedom and techno.

At the time, I had just started a Master’s, working shifts at a cocktailbar in Kreuzberg, getting to know Berlin’s nightlife and subcultures that came with it. Still wondering, still unsure about my path, still wandering—my peak indecisive era (so far, knock on wood!), so to speak. This period, along with the feelings tied to it, is as strongly linked to my associations with the artist’s works as the attributes I’d use to describe them. It sometimes be this way.

Of course, not long after, I discovered that Goldin herself had lived in Berlin for several years, which only intensified the connection I felt with her oeuvre.

Although I don’t remember exactly where I first saw one of Goldin’s photographs, I know that it stuck with me. It resonated deeply, perhaps because of the time period in my life, but it definitely stirred something within me. It was one of those encounters where you feel an inner urge to dig deeper, to research, after setting eyes on something new yet somehow familiar.

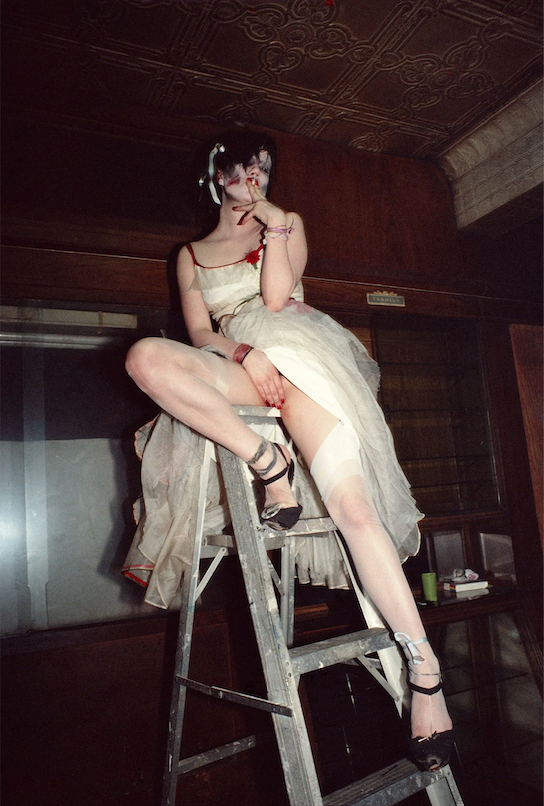

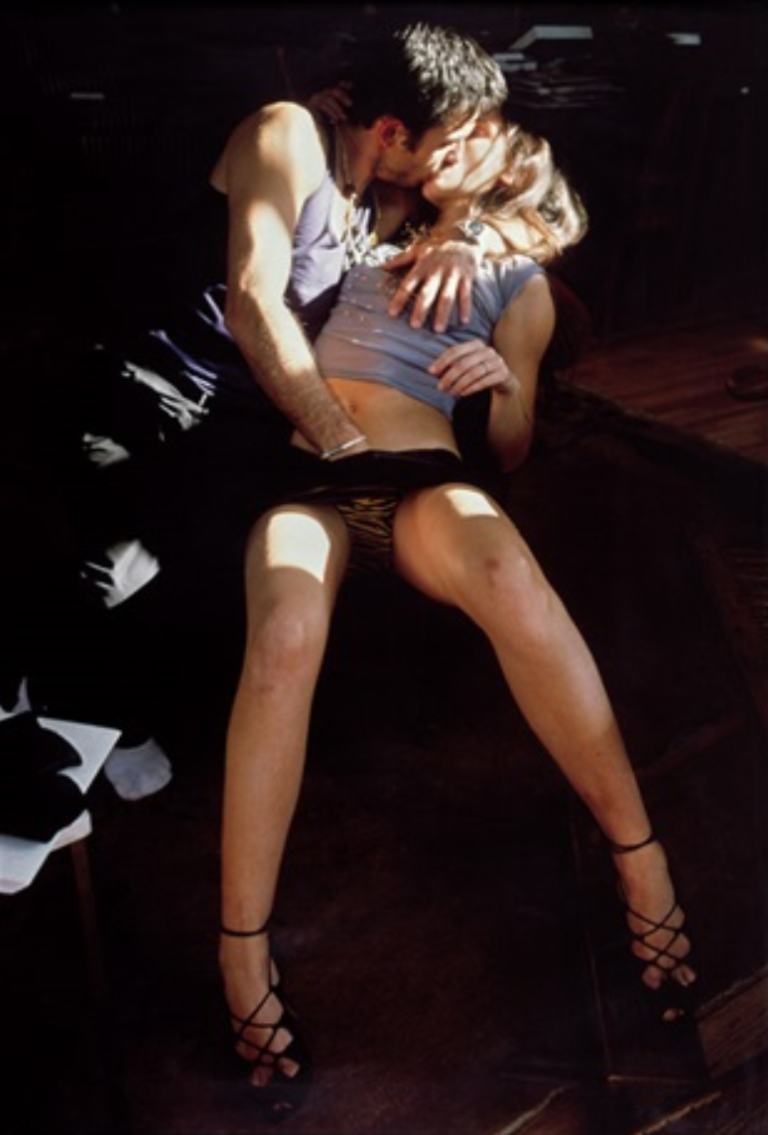

I vividly remember a conversation I had with someone about one of her photographs and her way of portraying people. The image was “Trixie on the Ladder, NYC” (1979), and we were discussing the degree of eroticism it displayed. Back then, as far as I recall, we came to the conclusion that it depended on the viewer—their disposition, as well as the context. Regardless of the artist’s intention, the photograph could be seen as erotic, but it just as easily might not be. Like a Rorschach test, the categorization would ultimately reveal more about the viewer than the image itself.

When I think back to that conversation now, I find it actually touches on quite an interesting duality that emerges when looking at Goldin’s photographs. Let me cook…

Goldin herself once said that her photographs arise from relationships, not from observations (1). And this may be the reason why they radiate such intimacy. So much so that the viewer sometimes feels like they are reading someone else’s diary. And I guess someone else’s intimacy can easily feel like eroticism to someone standing outside of it. You are being transported into another person’s reality so immediately and so vividly that the more you are able to immerse in it, the more you are likely to have the feeling that you shouldn’t—as though it’s somehow wrong. In fact, Goldin considered her photographs to be a public diary, capturing only what she herself experienced and lived through (1). And as a viewer, you can feel the authenticity behind them. These images are her perspective—one of many, but undeniably hers. Her world, her truth, her life, which she and her protagonists so generously invite us into:

Images of intimate scenes of or with close friends, parties, and also tackling troubling topics like addiction, relationships (sometimes in all their toxicity), disease, death, politics—topics that would generally feel taboo in the public eye, or that the vast majority of people prefer to keep to themselves or even hide. Her works are proof of a life dedicated to vulnerability, time and time again.

One thing that keeps the spectator from feeling like a voyeur (besides, of course, the fact that the artist is displaying them publicly) is the captured crudeness of reality which—weirdly and paradoxically—feels like the artist’s consent for the viewers to take part: honest, not beautified, rough everyday life, seldom staged if ever (at least compared to truly staged photography, like fashion photography, for example). But despite the honesty and relatability, the perceived edge between feeling like an intruder or an invitee that the viewer is dancing and balancing on remains.

Nan Goldin’s work is highly biographical. It’s inseparable from the person she is and all that makes her. Now, I can hear you thinking: „Thanks, Captain Obvious. We got it.“ But did we really?

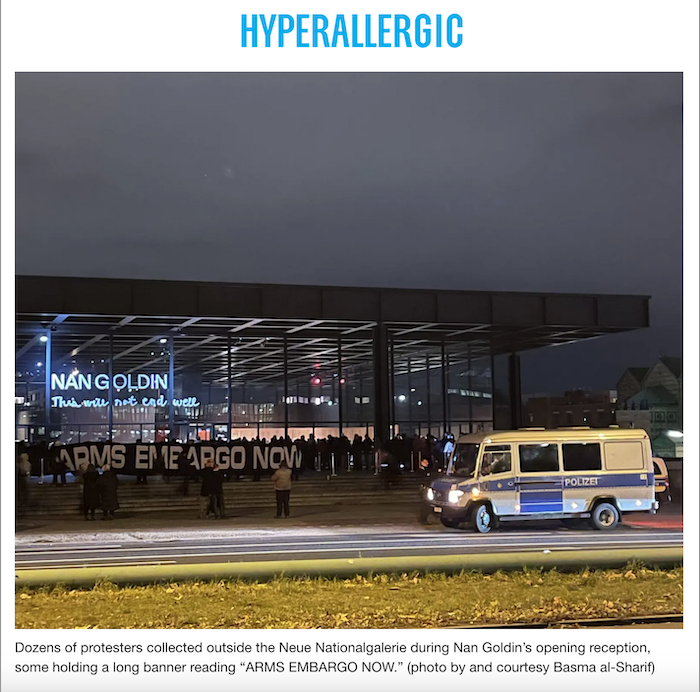

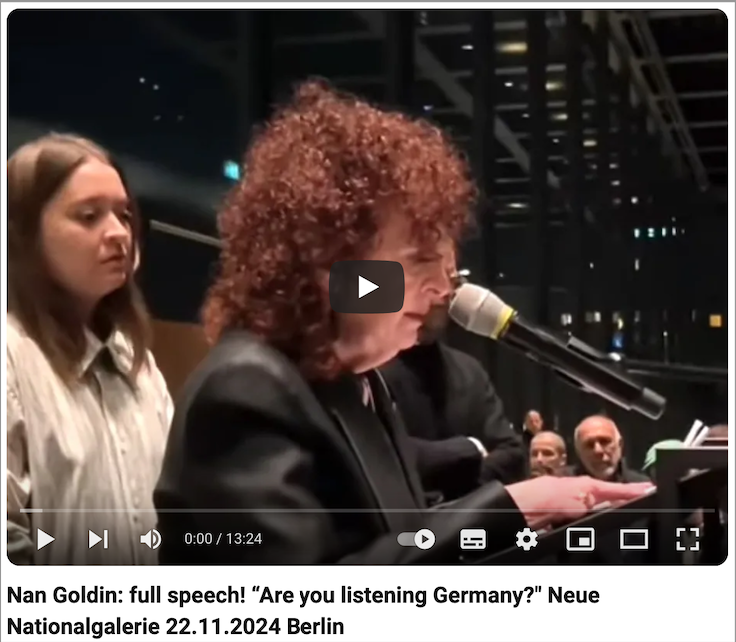

She seemed to feel the need to make this point clear again during her (what I would lean out my window to call) iconic speech at the opening of her recently inaugurated retrospective on November 22, 2024. The traveling exhibition, titled „This will not end well“, is still on view until April 6, 2025, at one of—if not ‚the‘—most important museums displaying contemporary art in Germany: Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie. And as many of us know, it debuted with a big bang due to the discrepancies between the artist’s, the institution’s and the interwoven state’s governing political positions regarding Israel’s ongoing soul-crushing war on Palestine.

During her opening speech, the artist highlighted Germany’s complicit role in this and also addressed the state’s inability to accept any form of critique on the matter. In response, Director Klaus Biesenbach made it clear in a brief speech delivered shortly afterward that the institution did not share the same opinion as the artist but believed it was important to give her the space to express her views freely (2).

“Why did I feel I had to talk tonight? This is my lifetime retrospective, but there is nothing in it from the past year. And that’s missing. The museum has kept its promise to allow me to talk, and I thank them. But they claim that my activism and my art are separate, even though that has never been the case. The last year has been Palestine and Lebanon for me. Since October 7, I’ve found it hard to breathe. I feel the catastrophe in my body, but it’s not in this show.” (2)

Lucky were the ones who made it to Goldin’s speech, as the queue for this museum’s openings is always longer than the one in front of Berghain, plus this time, in addition to your regular art enthusiasts—but not necessarily mutually exclusive—a large crowd of pro-Palestine activists attended the event as well. For the not-so-lucky ones, including myself, videos of the full speech were (and still are) circulating online shortly afterward (3).

What a fitting title for an exhibition then, not only given the global political circumstances but also considering what must have been happening behind the scenes during the preparations for this show. A symposium planned by the institution and scheduled to take place two days after the opening saw the withdrawal of Goldin and several other invitees because, as the artist later stated, she had never approved of the program (4).

It seems quite obvious—taking into account various German politicians’ comments in response to Goldin’s speech and the exhibition’s opening—that they would have preferred Goldin not speak at all („Why can’t I speak, Germany?“) or to somehow separate her art from her activism. Which only confirms some of the accusations made in the artist’s confrontational speech and made it all the more significant (4).

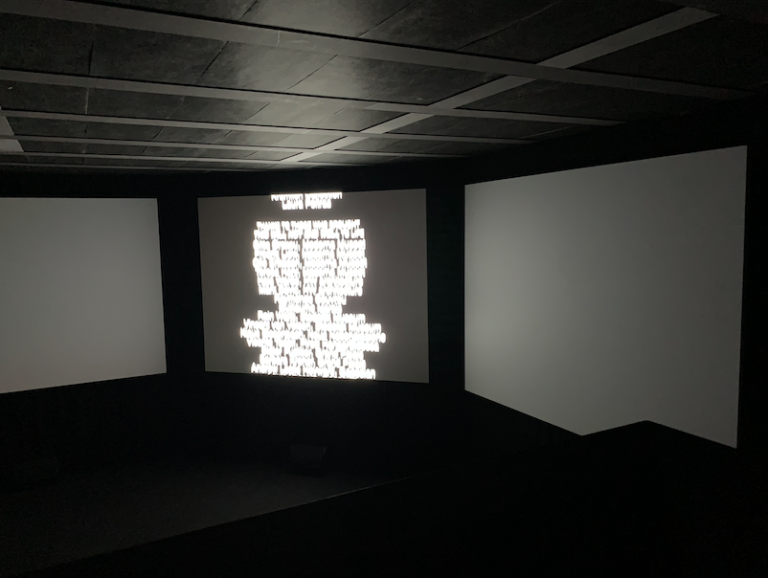

So her work was never meant to be seen separately from herself—ergo, her activism or political commitment. And the setup of the exhibition testifies to this. For someone who has never attended a larger exhibition by Nan Goldin, it feels quite refreshing to enter the exhibition space and not simply encounter walls filled with photographs. This would, no doubt, be a logical assumption when visiting an exhibition showcasing the work of a photographer. But Goldin has always been interested in a more dynamic, multimedia approach (5).

And so she has created her characteristic work series by assembling varying numbers of her photographs around a specific topic, presenting them to the viewer as slideshows. These slideshows are sometimes accompanied by music, fragments of interviews, voice-overs, or even video material. In this exhibition, these different work series are displayed on large screens inside black tents that are completely dark, offering visitors the chance to sit, stand, or lie down to fully immerse themselves in the works.

There are 6 pavilions, each designed by Hala Wardé to reflect the topic that the respective work series revolves around. Together, they form something that could be described as a small „village“ (5). What’s curious is that, while inside one pavilion, you can hear the faint sound of the others. It’s distant, but it creates the feeling that all the work series are somehow interconnected—just as the presented topics are deeply intertwined within the life of the artist.

Of course, all of the work series are highly intimate testimonies of her life and beliefs. One of them, „Sisters, Saints and Sibyls“ (2004-2022), is particularly personal—a 3-channel video installation in which the artist introduces us to her biography, showing how she grew up to become the person we see in the photographs. She narrates her troubled upbringing and family issues, accompanied by death and trauma, in a way that most people, if anything, would only share with their therapist, emphasizing the importance of making conversations about mental health issues safe, removing the shame, and taking them seriously.

Other work series addressing the highs and lows of drug consumption also include images reflecting Goldin’s involvement in the war against the Opioid Overdose Crisis. The series „The Other Side“ (1992-2021), which can be seen as an „homage“ (5) to the artist’s friends and members of the trans community, is explicitly dedicated to the memory of „all the trans sisters who we’ve lost to violence“. All the installations end (or begin, since they are displayed in loop) with the statement: „In solidarity with the people of Gaza, the West Bank, Lebanon, and the Israeli victims of October 7“.

Go check out the show if you have the chance. And maybe have some pictures taken at the museum’s Photomaton. It felt like the natural thing to do after visiting a photography exhibition:

Nan Goldin

„This will not end well“

Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin

Through April 6, 2025